What a Winter Looks like For a Honey Bee Colony

Whenever I’m in the garden during the summer months, I love spying on my Honey Bees pootling about the lavender bush. I think they’re truly incredible beings. Despite myself, I’ve also come to discover how dismissive I can be of the species when I’m tucked cosily away in my lounge one Winter evening, buried beneath piles of blankets, steaming cuppa in hand, surrounded by my cinnamon candle collection.

It begs the question, what might our little furry friends be up to during our excruciatingly long spells of abysmal -10°C weather?

I can’t say I’ve ever witnessed clouds of honeybees migrating to the southern regions of North Africa such as the likes of swallows and swifts.

So, are they then fond of the popular hibernation technique Bumble Bees resort to?

Also no.

As a matter of fact, Honey Bees, as I have come to realise, are a rather strange specimen regarding good ol’ winter survival. Unlike the many rodents, birds, bumble bees, bears and other animals that opt for the migration and hibernation tactics, Honey Bees prefer the comfort of their own hive, rather like the comfort of my lounge.

One should never underestimate the resilience of a Honey Bee. Instead, these hardy beasts actually stick it out through the thick and thin, come ice or snow.

Do Honeybees Like the Cold?

In short, no, they don’t. In fact, they despise it. However, hypothetically speaking if you were to peer into a hive mid January ( I sincerely advise against doing any such thing ) you’d find ginormous, but fairly peaceful, quivering ball of brown fur. Though they’re busy flapping their wings, incessantly trying to conserve heat, the queen will often drown her colony in powerful pheromones as a way of comforting them.

What’s Different in a Winter Hive?

There are some vital characteristics a winter Honey Bee possesses that differentiate them with their summer cousins. First and foremost, their size is noticeably bigger and plumper. They have a paunchier abdomen and aren’t afraid of shovelling down their honey stores if it’ll keep them alive during our bleakest weather events. They need strong, slow and controlled metabolisms in order to conserve as much of their energy as possible. Secondly, they’re incredibly robust and often flaunt longer life spans of about 4-6 months. Whereas, in comparison, a summer Honey Bee must make the most of a chaotic several weeks it has to live. Lastly, and most drastic a change is the tumultuous end to the male drone. When Autumn really begins to kick in, the drones are booted out of the hive which as you can imagine is a most unfortunate experience for them. You may think the female constituents of a bee colony to be a pretty savage alliance, however seeing as their top priority is the survival and security of the hive approaching Winter, drones are just another mouthful to feed. A waste of space…no offence gents. So, from around November to March, that hive is basically a sorority house that’s finally found a bit of peace and quiet.

How Do Honey Bees Stay Warm?

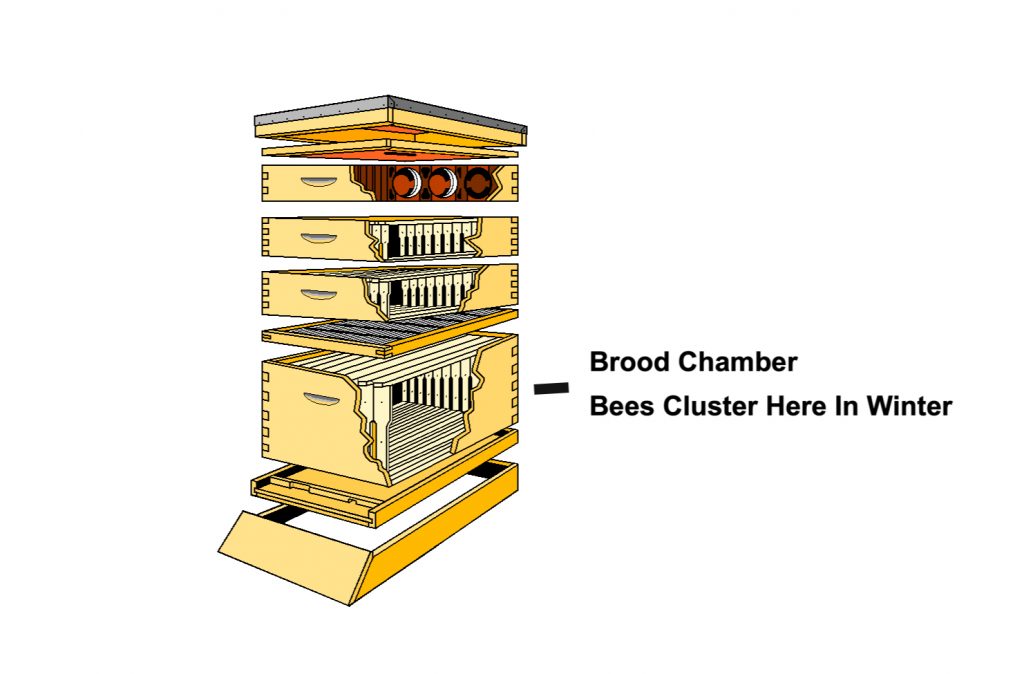

As for internal heating of the hive, Honey Bees favour methods of heat conduction ironically kindred to a human body shivering. Their natural instinct is to maintain a temperature of 35°C at all times. By doing so, large clusters of bees huddle together forming one large tight unit surrounding their queen and flap their wings at high speeds. She remains centre stage, in the middle of the crowd whilst the reverberations continue around her. She’s essentially the core of the boiler room whilst her fellow worker bees vibrate intensely.

What if They Need to Visit the Lavatory?

As with any part of the year, the hive’s lavatory is always outside. And as to be expected, Honey Bees only ever venture into the wintry wilderness when their bladder is on the brink of bursting. But, on these few occasions, when temperatures fluctuate above 10°C, they make the effort to crawl outside and deposit any waste.

Food Source and Honey Production?

Honey production is forced to come to an end as the winter months crawl nearer. Daylight hours shorten, available forage becomes severely depleted, and temperatures become unbearable for a honeybee’s muscles to contract thus they cannot fly to collect pollen and nectar. But this only heightens the importance of foraging during the Spring and Summer months when nectar supply is so plentiful. March through to October is completely devoted to honey production and building up a secure honey supply that’ll last through Winter. Therefore, if all’s well and the previous warmer months allowed for a productive honey season, our girls can enjoy feasting on their fresh stock of goodness at a later date.

Should I Be Doing Anything With the Hives During Winter?

We recommend, during the autumnal months approaching Winter to ease up on any intensive beekeeping. Generally, we finish harvesting honey in September to allow a healthy supply leftover for them to graze on in the Winter months. Bee colony maintenance such as Varroa mite treatment and securing the hive against harsher weather climates is a reasonable care plan approach for your apiary. Other than that, it’s best to leave the girls alone for the most part and save any beekeeping trips solely for the purpose of checking honey stores and hive maintenance.

You Can Buy Our Honey Here

Some More Interesting Honey Articles:

Is Honey Good For You, and if so, What Are The Health Benefits Of Honey?

Important Historical Figures In Beekeeping

- The Environmental Superiority of Local Honey: A Sustainable Choice for Our Planet - 12 October 2025

- The Sustainable Sourcing of Local Wildflower Honey: A Deep Dive into Ethical Beekeeping Practices - 8 October 2025

- The Differences Between Local and Shop-Bought Honey: A Comprehensive Exploration - 7 October 2025